The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 To comment on SPECIFIC PARAGRAPHS, click on the speech bubble next to that paragraph.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Throughout the 1990s, digital computing and network technologies were largely employed in office work, their cultural implications confined to niche realms for enthusiasts. If that decade’s new media art formed a vital artistic subculture, it was mainly isolated and self-referential, in part due to the artists’ fascination with hacking the medium, in part due to its position as the last in a long line of Greenbergian interrogations of the medium, and in part due to its marginalization by established art institutions. Artists like Vuk Cosic, Jodi, Alexei Shulgin, and Heath Bunting replayed early twentieth century avant-garde strategies while emulating the graphic and programming demos of 1980s hacker culture, before computers left the realm of user groups and became broadly useful in society.[1]

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 Today, in contrast, digital technology is an unmistakable presence in everyday life and is increasingly inextricable from mainstream social needs and conventions. Network culture is a broad sociocultural shift much like postmodernity, not limited to technological developments or to “new media.”[2] Precisely because maturing digital and networking technologies are inseparable from contemporary culture — even more than the spectacle of the television was from postmodernity — they must be read within a larger context. All art, today, is to one extent or another, networked art.

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 This investigation can’t be limited to online venues, but it also can’t be limited to “art.” Postmodernism called high and low into question (think of Warhol as the quintessential early postmodern artist, or later Barbara Kruger, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince) by bringing in products of the culture industry into art, but network culture levels that distinction utterly. Art under network culture dismisses the populist projection of the audience’s desires into art for the incorporation of the audience’s desires into art and the blurring of boundaries between media and public.[3] With the spread of knowledge work, attitude and a quick wit for fashion have become more important than knowledge of historical depth so, as Alan Liu suggests, whether a cultural artifact is cool or not matters more than its status in high and low (indeed, unless the object is first cool, styling it as high ensures that it will be seen as kitsch today).[4] Still, as a chapter in a book on networked art instead of, say, on networked cultural production, our focus here is on art. Nevertheless, we will also roam afield to a broader survey of cultural products, high and low, online and not (if it is possible to say that there is anything not online today in some form). Thus, this essay examines not only what is on Turbulence.org but also what is on television, on YouTube, or in the gallery.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 Specifically, this chapter looks at how networked cultural production draws on reality, from reality television to blogs to MySpace to YouTube to the art gallery. Reality art leaves behind formal structure and deeper meaning for a heightened sense of immediacy. This immediacy, however, is not so much authentic and present as mediated and dispersed. To speak of this work as “reality” media is not to imply it is not coded. On the contrary, the fascination with the real in “reality” media, be it reality TV, amateur-generated content, or professional “art” is constructed around specific tactics: self-exposure, information visualization, the documentarian turn, remix, and participation. Nor should we expect these transactions to be one way for if the distinction between high and low is tenuous at best, then it stands to reason that the discourse formerly known as art will also influence what was formerly considered non-art. After laying out a context for immediated reality, this essay will examine these five registers in a preliminary survey of the field. In looking at such art practices, it’s important to understand both how they fit into broader aspects of network culture and how they work within the discipline.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 Network culture is not a rejection of postmodernism but rather a shift or mutation that builds on it. Take aggregative works, for example, which elaborate upon curatorial art practices of the early 1990s or participatory art which draws on the “relational aesthetics” emerging at the end of that decade. Nevertheless, there is also a break and this break is not only with postmodernism but also with a long modernity: the new poetics of the real is distinct from existing models of realism, both the classical realism that first emerged in the eighteenth century, accompanying the bourgeoisie’s rise to power to mature during the nineteenth century, and the postmodernist realism of trauma, fragment, and ironic quotation.

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 In its subject matter, classical realism embraced everyday — as opposed to courtly or idealized — life. This matter-of-factness challenged the aristocracy’s dominance of the aesthetic realm, inverting the old order’s aesthetic of high themes and established commonplaces.[5] But more than that, classical realism was produced by an epistemological break. Until the eighteenth century, cultural producers saw invention as a matter of elaborating on convention and conforming to decorum, thereafter however, they would rely on internal capacities of their subjectivity, e.g. insight and original thought. In this, novelists like Henry Fielding or Samuel Richardson and genre painters like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin or, a century later, Gustav Courbet paralleled the investigations of philosophers like René Descartes, for whom truth was a matter of individual observation, and understanding the product of an individual comprehending the world through his or her senses. In taking the everyday and turning it into a work of art, realists demonstrated the transformative potential of the human imagination.

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 When compared to earlier forms of literature and art, realist works appeared formless, eschewing strict traditional structures.[6] This very absence of predefined structure underscored the primacy of experience over tradition. Still, realism relied on conventions to reinforce the notion that beyond everyday life lay universal truths. Take plot in the novel: if the novelist presented his text as a slice of everyday life, that slice took the form of a narrative arc that demonstrated, by example, the coherence and deeper meaning of everyday life. Or take the private nature of the novel’s narrative: by depicting the inner struggles of the individual in the world, novelists described the totality of life, not just its public face, thereby stressing the importance of the private over the public and giving new value to individual action and personal morality. Thus when Georg Lukacs lauded realist works expressing the totality of socioeconomic life, he articulated the basic principle behind realism (if in Marxist form).[7] Realism accompanied the rise of the bourgeoisie, so if signs now point to a new class structure emerging as, in developed countries at least, the dominant form of labor shifts from factory work to immaterial production and knowledge work, then we should not be surprised to see a new way of understanding the world emerge.[8]

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0

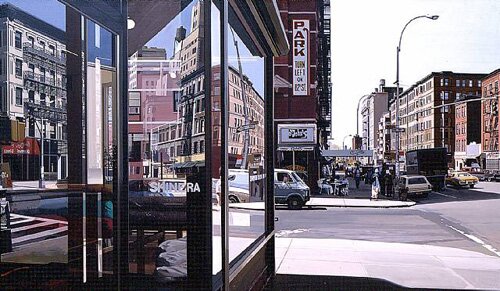

Richard Estes, Oenophilia, 1983

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

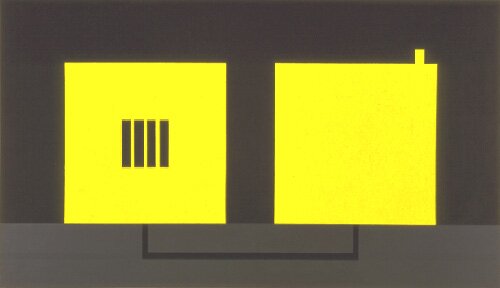

Peter Halley, Prison Cell with Smokestack & Conduit, 1985

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 Postmodernism, in turn, was a key transitional moment exploring the schizophrenic fragmentation of the real (together with the sign and the subject) under the pressures of mass media.[9] Superrealist artists such as Richard Estes induced a schizophrenic perception of surfaces and signs, a hallucinogenic reality exceeding the capacity of either the photograph or the eye, a condition that Hal Foster describes as “overwhelmed by appearance.” Appropriation artists like Richard Prince*, Sherri Levine, and (the early) Cindy Sherman critiqued how reality is constructed in media representation while questioning ideas of authorship and property. Simulationist artists like Allan McCollum and Peter Halley extended the idea of appropriation to create neutral works claiming to be void of emotion, originality or authorship, embracing instead the market and reproducibility in media. In the latter days of postmodernism, abject artists like Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Kiki Smith, Andreas Serrano, and (the later) Cindy Sherman hunted for signs of reality in the traumatic, exploring the violated and the defiled by simulating bodily excretions, wounded bodies, or damaged objects from childhood, but as Foster observes, they also worked in an artistic milieu from which emotion had been drained. For postmodernists, appealing to trauma discourse was a matter of simultaneously playing out the critique of the subject while calling for an identity politics.[10] Throughout, then, postmodern art was concerned with articulating the schizophrenic fragmentation of both sign and subject.[11]

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 The Immediated Real

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Each era, Jules Michelet observed, dreams the following. Postmodernism’s dream was of network culture.[12] For to declare the death of master narratives, postmodernist theory forged a new master narrative around networks of multinational capitalism.[13] Still, the role of networks was only nascent in postmodern culture — most obviously, the Internet was not yet privatized or significantly colonized by capital and mobile technology was still new — and the complicated nature of network culture — for example, the growth of open source, the rise of knowledge workers, the widespread piracy of informational commodities, the importance of bottom-up production, and the rapid decline of traditional informational industries such as newspapers — was as yet unforeseen. So just as postmodernity emerged after the process of modernization was complete, in turn network culture could only come after postmodernity had run its course. Today the fragmentation of the sign, the end of the subject, and the dissolution of any sense of authenticity in media are fait accompli. If postmodernism celebrated the shattering of the subject, network culture takes that shattering as a given.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 Today’s self emerges from the network, not so much a whole individual as a composite entity constituted out of the links it forms with others, a mix of known and unknown others it links to via the Net.[14] As its ground, instead of immediate, lived experience, the contemporary subject relies on the immediated real, a condition in which mediation is a given and life becomes a form of performance, constantly lived in a culture of exposure in exchange for self-affirming feedback.[15]

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Where modernity legitimated itself on the basis of an historical narrative and postmodernity used theory to critique that legitimation and to reflect on its own state in the world, network culture undoes any sense of history or theory.[16] In its stead is left only an immediated reality that eschews either legitimation or critique but just is. The critique of industrial society’s homogeneity that was common in art under modernism and postmodernism is now absorbed into management theory, the alienated factory worker replaced by the knowledge worker with the “freedom” of job flexibility (which also means no benefits or job security) and the privilege of self-expression as a member of the creative class.[17]

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 As management theory has absorbed critique, the market informs art more than ever. What use is the symbolic capital of theoretical resistance when real capital could be earned? Since the mid-1990s, artists have increasingly entered a new post-critical framework, concerning themselves with the cool or a return to the beautiful.[18] The art of network culture, then, operates within a culture that is rarely Utopian or oppositional but rather more concerned with its own position within the vast game of the network.[19]

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Self-Exposure

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 The importance of the immediated real to network culture manifests itself most clearly in the reality television show and the webcam. In the 1990s and early 2000s, shows such as MTV’s The Real World promised unmediated glimpses into everyday life. But, broadcast on a medium with long-established conventions, these swiftly degenerated into scripted productions like Big Brother and Survivor or in the case of shows like Fear Factor or American Idol became little more than rewritten game shows, incorporating cash prizes or the promise of media stardom to their contestants.[20] Still, reality television is now firmly incorporated in television culture, for example in the comedy The Office — which is framed as a reality television show — characters frequently address the television camera directly as if on such a show and maintain blogs on the show’s Web site. In 2005, in a crossover between art and reality TV, Marisa Olson auditioned for American Idol and maintained a blog about the process at http://americanidolauditiontraining.blogs.com.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 Reality culture is at its purest not on television but on webcam sites. In Jennicam, Jennifer Ringley offered an uncensored, constant glimpse into her personal life to the three to four million daily visitors. Like other webcam or, for that matter, the more recent lifestreaming sites, Jennicam manifested key aspects of reality culture: no narrative arc or any suggestion of a deeper meaning, but instead a glimpse into the private life of an individual hoping to expose himself or herself. This glimpse was not one-way; Ringley frequently reached out to her audience through e-mail and chat, a process that she made visible on Jennicam.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 The second webcam to transmit around the clock is Anacam, this time by an artist, Ana Voog. Broadcasting since 1997, like Jennicam, Anacam is a glimpse into Voog’s life, even if her project, unlike Jennicam, includes performance art, pointing to a breakdown between performance and life under the constant scrutiny of the unseen audience as connoisseurs and voyeurs. Voog, who engaged in sexual activity in front of the camera would get cosmetic breast implants in 1998.[21]

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 Beyond the webcam, immediated reality abounds throughout Internet culture. Blogs, social networking sites, and Twitter all offer platforms for self-exposure. Web sites such as eBaum’s World or YouTube do as well, in large part being made up of videos that claim to be true, such as scenes of people doing funny, stupid, or dangerous things or direct addresses to the audience, all done with the intent of appealing to an audience who would view them online. Viral marketers and media producers (e.g. Lonelygirl15 or Little Loca) have embraced this appeal to reality as well, utilizing the direct address to the audience and the amateur production values of net video.[22] Even pornography has recently lost its sense of fiction, narrative arc, and profit — an ironic note given that in the 1990s dot.com era pornography was considered the one reliably profitable Internet enterprise. Instead it is increasingly being produced by amateurs and uploaded for display on sites like XTube or 4chan.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 One of the more famous examples of self exposure in recent art is Untitled (2003), in which Andrea Fraser filmed herself having sex with a patron who paid $20,000 for the privilege, then displayed a video of the act in a gallery where editions of the video were subsequently sold. The work implicitly raised the question of whether the patron paid for sex with Fraser or to expose the act in the gallery. Contrasting this to Tracey Enim’s My Bed (1998) reveals the difference between the postmodern and immediated reality. Enim’s sexual exploits are recorded in her unmade bed, which in its studied dishevelment, is meant to align her work with abject art. Enim’s bed is framed by a purported nervous breakdown, pointing to a confused narrative in which the artist alternately boasts of and is disturbed by her promiscuous sexuality. The bed is key to the project, an index of Enim’s (sexual) performance and a device that serves to validate the project through its appeal to authenticity and presence. In contrast Fraser’s work is much more matter of fact, a calculated act of self-exposure to be reproduced in media.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Artist and theorist Jordan Crandall writes “In many ways this culture would seem to be less a representational than a presentational one, where we are compelled to solicit the attention of others, act for unseen eyes, and develop new forms of connective intensity — as if this were somehow the very condition of our continued existence, the marker of our worth.” Crandall also points to another aspect of showing, the desire to submit in the face of technologies of tracking and surveillance.[23] Under the rubric of “surveillance art,” a contemporary counterpart to Foucault’s reading of the panopticon, a number of artists — such as Crandall himself, Diller and Scofidio, the Institute for Applied Autonomy, and the Bureau of Inverse Technology explore this drive to submit as an object of critique.[24]

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 Surveillance art often ascribes the role of the watcher to a mysterious, unknown power. The Eyes of Laura (2005) by artist Janet Cardiff is an exception. For this work, Cardiff constructed the character of Laura, a security guard who had become obsessed with watching a thief she nicknames “Rabbit.” As presented, the project gave no clue that it was a work of art, even allowing visitors to control a security camera at the sponsoring Vancouver Art Gallery (the Gallery’s sponsorship or location was not identified on the site). If the project may have ultimately been too contrived to maintain the viewer’s suspension of disbelief, it nevertheless examined both surveillance and exposure (Laura’s desire to talk about her life and activities) under immediated reality while toying with our definition of what is real.[25]

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0

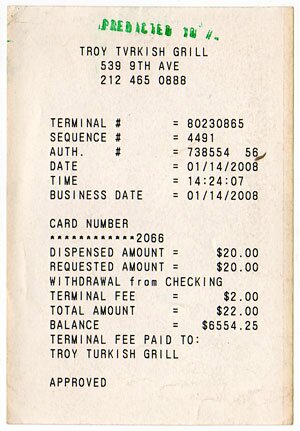

Burak Arikan, MyPocket, 2007

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 0 Like Cardiff’s The Eyes of Laura, Burak Arikan’s MyPocket (a 2007 Turbulence Commission) mixes surveillance and self-exposure, disclosing three years of his financial records to the world and employing software to predict his future spending habits. MyPocket questions the finance industry’s insistence on the transparency and management of our finances even as the industry insists on its opacity to us. Moreover, in introducing the capacity to predict his own future spending through software, not only does Arikan mimic the acts of such corporations, he demonstrates how our choices are constituted within a network of information, in this case financial.[26]

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 Infoviz

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 MyPocket brings us to information visualization (infoviz). Just as the functional software of the 1990s replaced the programming demos of the 1980s, so works consisting of dynamic visualizations of quantified data replace the self-referential new media art of the 1990s.

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 To some extent, infoviz is the most directly imbricated of all the registers of immediated reality in computation. Artists operating in the other registers of immediated reality take digital technology and networks as a given, generally relying upon it much as “prosumers” might, as a set of technologies to build works out of without necessarily getting deep under the surface. In contrast, infoviz generally demands that artists get involved in programming, turning to coding environments such as the programming language Processing or to complex, professional environments such as GIS mapping software.[27]

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0 Infoviz has received much attention recently — most notably in the 2009 MoMA show Design and the Elastic Mind — and thus warrants less discussion here than other aspects of immediated reality. Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar’s I Want You to Want to Me (2008) is an example of this sort of work, building on acts of self-exposure by others. Captivated by how members of online dating sites describe not only themselves but the traits they desire in their mates with brief phrases, Harris and Kampvar present this data on high-resolution touch screens.[28] Yunchul Kim’s (void)traffic (2004) is another example of infoviz, utilizing ASCII characters to represent data traffic, thereby evoking the idea of a “black-and-white digital organism” or the “surface of the sun.”[29]

¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen, Movable Type, 2007

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 But infoviz’s downfall is its spectacularization of data and faith in technology. For if infoviz is the clearest inheritor of modernism, its origins are not the disruptive, avant-garde modernism of the 1920s but the modernism of the 1950s and 1960s. Aiming for a reconciliation of thinking and feeling under the bureaucratic technologizing of the senses, postwar modernism was the visual representation of the Fordist corporation. In turn, infoviz corresponds to the “efficient market hypothesis” prevalent in the last decade in which the purported wealth of information easily available to us over networks allows the market to operate efficiently and rationally. Take, for example, Ben Rubin and Mark Hansen’s Movable Type, (2007) a grid of 560 vacuum-fluorescent display panels mounted in the lobby of the New York Times building. Each panel displays information mined from the day’s stories, the paper’s archive, and the activities of the visitors to the nytimes.com web site.[30] Far more than any late modern painting, this work advertises the company’s ability to control and efficiently extract information, turning it into an object of wonder. Claiming the ability to create new user interfaces, infoviz is often the purview of design firms or programmers and can be sponsored by venture capital. It can be hard to tell the latest art project from the latest startup.

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0

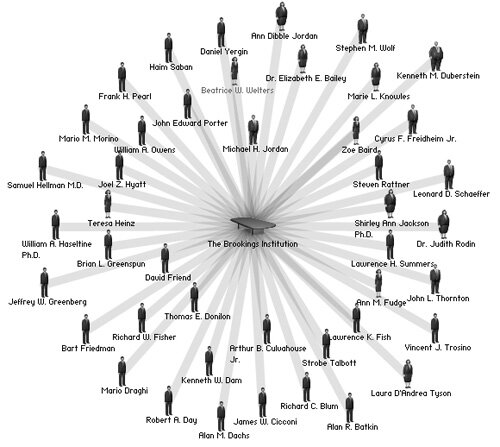

Josh On, They Rule (2004)

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 Tactical media activists have created politically progressive uses of infoviz. Spurred by Mark Lombardi’s elegant pencil drawings of networks of scandals in the late 1990s, they set out to reveal hidden power networks and critique in “counter-geographic” projects such as Bureau d’Etudes’ The World Government (2003) or Josh On’s They Rule (2004). Such works aim to unpack the complex weave of network power, nevertheless, if intriguing, such projects can be hampered by reducing network power to mere relationships.[31] Agency and intentionality may remain unclear while the work remains an object of fascination.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 0

Scott Hug, Consumer Mood, 2009

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0

Scott Hug, U. S. Life Evaluation, 2009

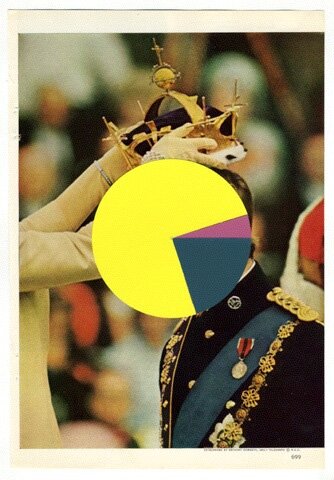

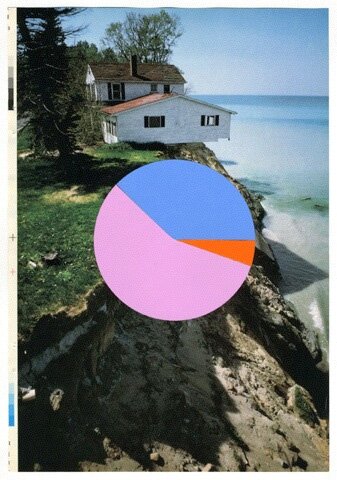

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0 Scott Hug critiques both infoviz and network culture’s pervasive obsession with data today in Personal Finance, State of the Nation, Consumer Mood, U.S. Perception on the Morality of Homosexual Relations, and Death Penalty (2009), a series of pie charts that he paints on wood or superimposes over images lifted from old issues of National Geographic, using colors from forecasts of pallets in upcoming fashions. Taking data from Gallop polls out of its context and stuffing it into the banal form of the pie chart, Hug parodies how infoviz makes data an object of rapt aesthetic fascination while also critiquing network culture’s overall obsession with data as form.

¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0 The Documentarian Turn

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Where infoviz aestheticizes quantified data to represent a vision of reality, documentarian art presents reality as a narrative. Of all the registers of the immediated real, only the documentary maintains narrative and coherence as its hallmark. But in order to maintain that coherence, documentarian art treats reality as something to script and manipulate, not just to take as given. In this, the documentarian turn is the inheritor of fiction today. For example, in the writing of David Foster Wallace, the lines between fiction and non-fiction are difficult to discern, especially since both are annotated with copious footnotes, as important to the text as the main narrative. But documentary’s rise is easiest to see in film where, during the last decade, it has become popular with critics, audiences, and filmmakers. Films such as Grizzly Man, Supersize Me, March of the Penguins, An Inconvenient Truth, and Fahrenheit 911 form a growing strain in cinema. More and more it is also a field for the auteur for whom the material serves as a canvas for a highly scripted interpretation of reality. Werner Herzog, to take one well-known documentary filmmaker, uses it as the basis for a “poetic, ecstatic truth.”[32] As the Internet makes information sharing about documentaries easy, their scripting is rapidly exposed, as for example in William Jirsa’s review of a documentary he appeared in, Werner Herzog’s At the End of the World (2009), or in the numerous responses to Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me (2004) and Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (2002).

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 One of the dominant forms of art under network culture has been photography reproduced at large scale, especially that of Thomas Demand, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hutte, Thomas Ruff, and Thomas Struth, all of whom studied in Düsseldorf with Bernd and Hilla Becher in the mid-1970s. The works of these photographers, along with those of a number of other photographers such as Jeff Wall or Hiroshi Sugimoto not only rival nineteenth century salon painting in size but also in their depiction of a constructed reality. Producing works so vivid and sharp requires effort and manipulation on the scale of Herzog’s “ecstatic truth” and many of these photographers take liberties to produce the vision of the world they want to create even if it needs to be constructed in post-processing. Demand, the youngest of the Düsseldorf school members, constructs sets, generally out of paper, that appear almost indistinguishable from the reality they aim to represent (the almost is key), thus questioning the constructed nature of the documentarian turn.

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 0 But such photography, produced for the gallery and the coffee table art book is transitional, its self-proclaimed status as the successor to painting as the pinnacle of visual art problematic. With the breakdown of traditional structures, “feral institutions” particularly rich in Los Angeles where The Center for Land Use Interpretation investigates ignored industrial, military, and touristic uses of the landscape, The Institute For Figuring explores mathematical figures, the Velaslavasay Panorama displays panaromas, the Los Angeles Urban Rangers appropriate the figure of the park ranger to lead counter-tours of the city, and AUDC (originally in Los Angeles but now in New York) explores contemporary culture through seemingly unreal but true situations interpreted through theory and through architectural drawings, models, and photographs.[33]

¶ 42 Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

Museum of Jurassic Technology, The Sonnabend Model of Obliscence

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 If some feral institutions (The Center for Land Use Interpretation, AUDC) engage in research, however non-traditional, others create fictional (or partly-fictional) realities, often so elaborately constructed as to break down the bounds between art and reality, artist, curator, the real, and the constructed. Such work draws on both documentarian and postconceptual art practices. Beginning in the late 1980s artists like Ilya Khabakov and Mark Dion moved away from the uncomplicated models of appropriation and simplistic ideas of institutional critique practiced by postmodern artists toward more complicated relationships. Generally, the departure point for this generation, epitizomed by the Museum of Jurassic Technology, would be the sixteenth and seventeenth century cabinet of curiosities or wunderkammer, the prototype for the museum, in which natural and man-made wonders would be juxtaposed in an idiosyncratic system, valued for their capacity to stimulate the senses. If the cabinet of curiosities parallels the post-critical obsession with beauty, it does so as a studied anachronism, displacing beauty and wonder from the present to another time when they were not yet commodified. In returning to the origins of autonomous art and the museum, such work recalls a time before the modern concept of art, when art was still integrated with life and not divorced into its own sphere, even as it anticipates the dissolution of art under network culture. Still, if the original cabinet of curiosities was an instrument of propaganda, conveying the assembler’s ability to control the world, the new cabinet of curiosities is conceived as flawed, its knowledge fragmentary, incomplete and even outright false. Thus if these new cabinets of curiosities aim to inspire wonder, it not so much the unmediated wonder that the original wunderkammer created or even a wonder at the boundaries of art dissolving but rather a perceptual challenge forcing us to question the nature of immediated reality.[34]

¶ 44 Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

The Chadwicks, The Genretron (2008)

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 To take another example, the Chadwicks (Lytle Shaw and Jimbo Blakely) collaborate as descendants of a (fake) family of “eminent connoisseurs, sea captains, naval engineers and amateur historians,” tracing its origins to the era of Dutch expansion. In a bad faith effort to convince the public of their rights to various claims, the Chadwicks produce somewhat damaged or even outright deranged historical reconstructions that call into question the nature of the immediated real. To confuse matters, in a recent publication, The Chawick Family Papers: A Brief Public Glimpse, Sina Najafi, the editor of Cabinet magazine, launches a mock attack on the project as a way of discussing their work.

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 Tactical media also engages in such fiction, for example, the Yes Men (one of whom, Igor Vamos, has also been involved with the Center for Land Use Interpretation) have produced fake Web sites and falsely posed as spokesmen for government entities and corporations to deliver their biting critiques. Examples include a parody Web site for the World Trade Organization (http://www.gatt.org/), a Web site on a fake Exxon product that would convert the bodies of billions of climate-change victims into oil (http://www.vivoleum.com, shut down by the ISP) and a fake printed issue of the New York Times (and accompanying Web Site, http://www.nytimes-se.com/) with the headline “Iraq War Ends.” Beyond delivering their messages in a subversive and humorous way, such work leads its audience to question how easily media can construct meanings for the purposes of dominant power.

¶ 47 Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0 The Artist as Aggregator

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Immediated reality overloads us with information. Instead of interpretation, however, in network culture, aggregation becomes the prime strategy for dealing with information. Thus, mass media such as newspapers and television networks have ceded their position of cultural power to software-based aggregators like Google News (which brags that “The selection and placement of stories on this page were determined automatically by a computer program”), Amazon, Netflix, and iTunes. These software engines automatically select and deliver results based on visitors’ interests, giving access to vast, unprecedented quantities of information.[35] But aggregation also has a DIY-side. Not only do sites such as Amazon, Kaboodle, Youtube, Last.fm, Imagefap, Rhizome, and Flickr encourage users to curate and make public lists of their selections, profile pages on social networking sites are all but constituted by ones social connections, cultural interests, and professional affiliations. The result is the most common manifestation of “networked publics.” More than any testimonial or self-confession, aggregation becomes a means of describing the connected self in immediated reality. Blogs, too, highlight the change in authorship that aggregation creates. If bloggers use blogs for self-exposure, they also frequently fill them with reblogged items from other blogs or comments on other blogs, Web sites, technological products, articles, books, and so on. This is exacerbated in social bookmarking sites like Delicious, FFFFOUND! or Tumblr, the latter designed for short-form blog entries generally based on reblogged photographs, quotes, links, audio, or video. Often the only comment is the context in which the work is curated. Artists — particularly “pro surfers” (more on these later) — also make such lists. Take for example Guthrie Lonergan’s Myspace Intro Playlist, a curated collection of short video clips by individuals introducing themselves to their MySpace audience (hence an aggregated collection of self-exposing videos).

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Under network culture the artist as aggregator increasingly replaces the earlier artist as producer. In this register of networked art, artists draw both on earlier curatorial art practices but also on the DIY forms of aggregation common to network culture. Such art practices generally address consumption in a more positive way than under postmodernism when artists tended to see consumption as an activity for uncultured individuals, lacking in reflection and easily accepting of media messages. Postmodern artists such as Richard Prince and Jeff Koons depicted consumption as an ecstatic activity undertaken by cultural dupes. Such work was always somewhat cynical as it marketed critical distance as a luxury product (notoriously, one of Richard Prince’s works was the first photograph to sell for over a million dollars), drawing on the tradition of art as non-alienated.[36] But in the late 1980s and early 1990s, art became subject to a Bourdouvian sociological critique just as the art market reached new heights to become one of the most delirious forms of consumption. At the same time, artists began to engage in curatorial practices, as for example, Damien Hirst did in his Freeze show of 1988, in which he curated the works of fellow students.

¶ 50 Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0 Today, curatorial works are an accepted part of art practice and artists understand consumption as a back-and-forth phenomenon and see the market not as a place for capital but rather for human interaction, an art version of the peer-to-peer forms of production and trade at Internet sites like eBay and Etsy. In this model, both producer and consumer now have agency and the ability to shape their lives positively.[37]

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0

High Desert Test Sites, Noah Purifoy Site, photo by Guy Lombardo

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Take High Desert Test Sites, for example, where artists Andrea Zittel and Lisa Anne Auerbach work with dealers Shaun Regen, John Connelly, and collector Andy Stillpass to create a weekend-long event in the Mojave desert composed of experimental art sites but also barbeques, swap meets, and local activism.[38] Or another work by Scott Hug, the annual zine K48 (and the related blog, http://thek48bullet.blogspot.com/), in which he shows not only his own work but also works by other artists — including CDs of music — that he finds interesting. If K48 affirms self-expression, that expression is as much made up of the content he aggregates as it is by the art he produces. One more example might be Random Rules: A Channel of Artists’ Selections from YouTube (2009) in which Marina Fokidis assembled a group of artists — Andreas Angelidakis, Aids 3D (Daniel Keller and Nick Kosmas), assume vivid astro focus, Pablo Leon de la Barra, Eric Beltran, Keren Cytter, Jeremy Deller, Cerith Wyn Evans, Dominique Gonzalez Foerster, Dora Garcia, Rodney Graham, Annika Larsson, Matthieu Laurette, Ingo Niermann, Miltos Manetas, Ahmet Ögüt, Angelo Plessas, Lisi Raskin, and Linda Wallace — to put together playlists of work that they like from YouTube.[39]

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0 Other artists are “pro surfers,” as Marisa Olson calls them, seeking out banal, badly-designed elements of the Web vernacular under a seeming suspension of aesthetic sensibility. The “surfing club” at nastynets.com emerged as the epicenter of this movement in 2006 (in itself it is not that distinguishable from sites like www.worstoftheweb.com or 4chan.org for that matter) and has more recently been joined by www.spiritsurfers.net.

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0

Oliver Payne and Nick Relph, Ash’s Stash, 2007

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 But like self-exposure, infoviz, and the artist as documentarian, intents may vary. The role of the artist as aggregator can also be cynical, reveling in the market. Take Nick Relph and Oliver Payne’s Ash’s Stash (2007), in which the artists presented a collection of ephemera from gallerist Ash Lange’s collections displayed in an installation aping a Prada Store at Art Basel Miami Beach. Critical distance was not so much hard to find as absent altogether.

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0 Remix

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 0 Building on the artist as aggregator is artist as remixer. In the contemporary milieu of networked publics, the traditional relationship of consumer and producer is undone. Amateur-generated content — often based on remixing content from more traditional media sources — has proliferated on the Internet, particularly in the video sharing site YouTube and photo sharing sites like Flickr or deviantArt as well as on blogs. Such work is avidly consumed by other amateurs who, in turn may remix it to produce second-order remix projects.

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 If remix thrives on using appropriated work, unlike postmodernism, it takes appropriation as given. In postmodern appropriation art, reuse was ironic, undertaken with a high degree of Oedipal self-consciousness. As Sherri Levine reappropriated earlier photographs by Walker Evans or Richard Prince blew up magazine advertisements to display in museums, they hoped to critique the authorial status of past masters. But appropriation artists, most notably Duchamp, still worked within an established tradition of art, drawing on avant-garde models of appropriation and framing. In their method originality was still critical, both as an institution to critique and as a crutch — for Duchamp, after all, the urinal is nothing until it is signed. Thus, if Levine’s work questioned Enlightenment notions of the author and originality, those notions are long ago obsolete.[40] For when pasting images from the Internet into PowerPoint or reblogging a favorite image on Tumblr is an everyday occurrence, appropriation becomes casual. Such postmodern works, then, were transitional. Relying on authorship and originality as departure points is no longer productive.[41]

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0 Nicolas Bourriaud suggests that this lack of regard for originality is precisely what makes art based on remix (his word for it is postproduction) appropriate to network culture. In contrast to postmodern artists, Bourriaud explains, artists like Pierre Huyghe and Douglas Gordon no longer question originality but rather instinctively understand artworks as objects constituted within networks, their meaning given by their position in relation to others and their use.[42] Like the DJ or the programmer, such artists don’t so much create as reorganize.[43] Crucially, remix takes place at a moment when globalization and the spread of historical information is pervasive due to the spread of the Net. “The artistic question is no longer,” Bourriaud concludes, “”what can we make that is new?” but “how can we make do with what we have?” In other words, how can we produce singularity and meaning from this chaotic mass of objects, names, and references that constitutes our daily life?”[44]

¶ 60 Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 Mark Leckey, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999

¶ 62 Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0 Mark Leckey, who operates in the gallery and the museum, but also has a MySpace page, is a veteran of remix, producing a seminal video in 1999 entitled Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore out of found footage of British dancers in the 1970s and 1980s, in which he uncovered the ritualistic aspects of dance culture. More recently his performances have consisted of lectures on theories of networked culture (such as Wired Magazine editor Chris Anderson’s The Long Tail) that traverse a litany of references from high art to pop culture. Leckey’s goal, as he proclaims in the statement he filmed for his Tate prize nomination, describes the poetics of network culture in a nutshell: “to transform my world and make it more so, make it more of what it is.” In Made in ‘Eaven (2004), Leckey reproduces Jeff Koons’ mirrored Rabbit sculpture; as the vantage point zooms in on the sculpture, Leckey’s own studio is revealed in a computer-rendered three-dimensional model.

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Remix can take many forms, not only in audio or video. In Diary of a Star (2004-2007) Eduardo Navas sampled The Andy Warhol Diaries on a blog as a means of reflecting on the role of celebrity and privacy on the Web. Concluding that in projects like The Last Supper, where Warhol’s brilliance shone as he mimicked the mimickers, Warhol would have made the “the perfect Web flâneur.”[45] Navas links to the sites that Andy would have explored if he had been able to browse the Web based on the entries in the Diaries.

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 0 Its worth noting that there is no particular injunction against the use of material from any era but the elements artists choose to remix tend to be relatively contemporary.[46] The nostalgia culture so endemic to postmodernism has been undone, the world still in the throes of modernization is long gone. Unable to periodize, network culture disregards both modern and premodern equally.[47]

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0 Besides just aggregating it, pro surfers also remix the web vernacular. Scarlet Electric’s MrsCoryArcangel.com, John Michael Boling’s www.gooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooogle.com and Guthrie Lonergran’s The Age of Mammals are all examples of pro surfer creations.

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0

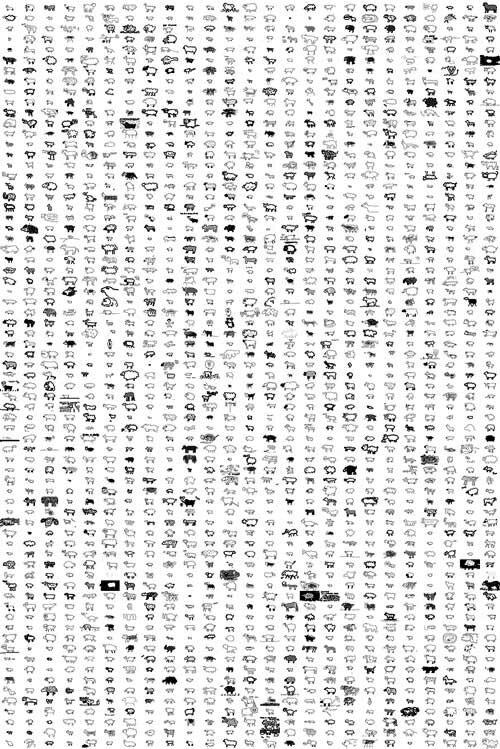

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 0 Oliver Laric, 787 ClipArts, 2006

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 0 Oliver Laric, Versions, 2007

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 0 Oliver Laric is one of the most adept artists working in remix today, elaborating on the genre as it emerges on Internet sites, most notably YouTube. Laric, who generally presents his own work online treats amateur videos as found media loops. In 50 50 2008 (2008), he remixes YouTube clips of amateurs riffing on hips by 50 Cent to form one continuous song, itself a remix of an earlier work he did. In 787 ClipArts (2006), he assembles 787 clip art images into a one minute five second loop, forming a continuous video-loop that brings together all races and activities in one fluid mix, demonstrating not only his ability but also hinting that everything that can already be done has been. In Stevie Wonder Duets (2007), he juxtaposes videos he finds on YouTube of Stevie Wonder songs, one instrumental, one vocal, allowing us to recognize the slippage of time between the renditions only to release them back onto YouTube. As Marisa Olson suggests though, it seems that Laric aims to send his work back into the Net, where it came from.[48] Finally, in Versions (2009), Laric produces a narrative that seems a bit like Leckey’s performances, a theoretical work at times reasonable, at times perhaps a bit preposterous, ranging across doctored photographs of Iraqi missiles, illicitly videotaped and pirated movies, celebrity heads grafted onto porn stars and so on. Remix, Laric points out to us, allows an infinity of parallel worlds to proliferate. Nevertheless, what remix amounts to besides delirious production, be it in the vernacular Web production celebrated by the pro surfers or the carefully orchestrated work Laric does, is as yet unclear.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0 Participation

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 0 First formulated by Bourriaud as “relational aesthetics” at the turn of the century, participatory art is open-ended, the author left to the task of programming by determining the code for the viewers’ actions. Take one of the foremost practitioners of participatory art, Rikrit Tiravanija, who fills galleries with stacks of cardboard boxes containing soup or pudding for visitors to cook and eat and constructs remixes of famous architectural structures (e.g. the Schindler House made out of mirror glass, the Maison Dom-Ino made out of wood) in which he encourages audiences to participate, create, and engage in events.[49]

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0 Relational aesthetics, which began in the early 1990s, anticipates the development of networked publics and Open Source culture a decade later. Encountering user-generated content on sites like Flickr and deviantART as well as commons-based peer produced software such as the Apache Web server, Linux operating system or Drupal content management system is no longer unusual but rather is part of everyday life. Coupled with a sustained underground pirate movement that disregards and fights against copyright ownership, “Internet free culture” points toward a future in which information loses its status as a commodity and, by extension, capitalism withers away. Conversely, the present lack of open, public alternatives to sites like Flickr or deviartART hints that free culture may never arrive and that unpaid peer production may become yet another vehicle with which capital colonizes everyday life, marshaling our free time into work. Just as disquietingly, participation can become a vehicle for conformism, as the phenomenon of flash mobs, created by Harper’s Magazine editor Bill Wasik, as a means of testing the gullibility of hipsters, proves.[50]

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 0 Participatory art at its best embodies the Utopian ambitions of Internet free culture and its invitation to anyone to participate. Thus, to take one example, even if it is an institution for Internet art, Rhizome.org is also a club that anyone can join, operating, in intent at least, as a free forum. At Telic Arts Exchange, a non-profit networked art initiative in Los Angeles, the “Public School” is a “school without a curriculum,” in which individuals propose classes that others can take.

¶ 75 Leave a comment on paragraph 75 0

Aaron Koblin, Sheep Market, 2006

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 Other artists work with more directed forms of audience participation, some of which explore the relationship between participation and the market. For example, at http://dziga.perrybard.net/, Perry Bard invited people worldwide to participate in recreating clips of Dziga Vertov’s 1929 Man with a Movie Camera. In the Sheep Market (2006), Aaron Koblin paid 10,000 workers (“mechanical turks”) on Amazon.com $0.02 to “draw a sheep facing the left” to produce a massive landscape of sheep. In collaboration with Takashi Kowashiba, Kolblin also produced Ten Thousand Cents a representation of a hundred dollar bill composed of 10,000 images, each drawn by one of Amazon’s mechanical turks for a penny.

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 0 Networked, But For What?

¶ 78 Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0 The goal of this chapter is neither to laud nor condemn network culture and the art of immediated reality but rather to take stock of it, drawing on both historical and theoretical understanding, even if that goes against the grain of network culture.

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 Under modernism, too much of what started out as oppositional wound up being employed as the latest visual technology for capital. Think of Moholy-Nagy’s trajectory from Constructivism to teaching how to design advertisements and products at a school of design or Gropius’ journey from Communism to corporatism. Worse yet, the oppositional stance of postmodernist art was often cynical, calculated for an art market that valued “resistant” art. It is still unclear what networked art’s broader historical role will be. Sometimes Utopian or critical it, too, is little more than a cheerleader for the technology sector or for the rise of knowledge work. A coherent vision of a socially progressive networked art — or even a socially progressive understanding of network culture — is still lacking. If we are to avoid networked art becoming just so much bling, turning into endless stimuli for our rapt fascination, be it on the Web or in the museum, a new critical perspective on this work is still urgently needed.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 0 * The author wanted to include Richard Prince, Untitled (Cowboy), 1987 but Richard Prince’s studio turned down our request for reproduction.

¶ 81 Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0 Endnotes

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 [1] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001).

¶ 83 Leave a comment on paragraph 83 0 [2] If, following Fredric Jameson, the colonization of all parts of life by capital drove the postmodern turn, the colonization of all parts of life by telecommunications, digital technology, and globalization drives the emergence of network culture. Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Capitalism,” New Left Review 146, (1984): 59-92. On the importance of the network today see and Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed. (Oxford ; Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2000) and Kazys Varnelis, “Introduction,” The Meaning of Network Culture. A History of the Contemporary, http://varnelis.net/network_culture/introduction.

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 [3] Kazys Varnelis, “Conclusion. The Meaning of Network Culture” in Varnelis, ed. Networked Publics (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 150.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 [4] Alan Liu, The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0 [5] Ian P. Watt, The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 9-34.

¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0 [6] In this, modernism can be seen as a subspecies of realism, representing individual interpretation of universal truths more thoroughly than could be done within the strictures of mimesis.

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 [7] Georg Lukacs, “Realism in the Balance,” in Ronald Taylor, Aesthetics and Politics: Debates Between Bloch, Lukacs, Brecht, Benjamin, Adorno (New York: Verso, 1980), 28-59.

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 [8] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 289-294. Liu, The Laws of Cool, 14-76.

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 0 [9] Generally speaking, where modernism, like realism, still holds out of the promise of a unified subject and a whole sign, postmodernism abandons that.

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 [10] See Foster, “The Return of the Real” in The Return of the Real (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996), 127-170 and Whitney Museum of American Art, Abject Art: Repulsion and Desire in American Art, Selections from the Permanent Collection, June 23-August 29, 1993, (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 1993).

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 [11] Jameson, 71-73 as well as Hal Foster, “(Post)Modern Polemics”, Recodings (Seattle: The Bay Press, 1985), 121-138.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0 [12] Michelet writes “Chaque époque rêve la suivante in Avenir! Avenir!, Europe 19 no 73 (January 15, 1929), 6 quoted in Walter Benjamin, “Paris, the Capital of the Nineteenth Century,” The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 97.

¶ 94 Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0 [13] Leo Marx “Live History? The Dilemma of Technological Determinism (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1994), 256.

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 [14] Varnelis, 154. See also Kenneth J. Gergen, The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life, (New York: Basic Books, 2000) and Brian Holmes, “The Flexible Personality. For A New Cultural Critique,” http://www.16beavergroup.org/brian/.

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 0 [15] This idea relies on Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the simulation, but in its very language, the simulation still holds out a premise that it is produced by the media industry for us to occupy indirectly. Immediated reality is produced by everyone, constantly, and the media industry’s influences fades in it, or rather is transformed.

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 [16] Margriet Schavemaker, Mischa Rakier, eds. Right About Now: Art & Theory since the 1990s, (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2007), 9-10.

¶ 98 Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0 [17] Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Verso, 2005).

¶ 99 Leave a comment on paragraph 99 0 [18] A foundational text for theories of beauty in art is Dave Hickey, The Invisible Dragon. Four Essays on Beauty in Art (Los Angeles: Art Issues Press, 1993). It is important to note that to avoid accusations of his definition of beauty being kitsch, Hickey makes it cool by framing it within a discussion of Robert Mappelthorpe’s photography. With Harvey’s guidance (along with that of the likes of Peter Schjeldahl and Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe), abject art — from Mappelthorpe to Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ to Damien Hirst’s sharks — was reconstructed as beautiful, leaving behind postmodernism for the cool art of the post-critical era. See also Bill Beckley and David Shapiro, eds. Uncontrollable Beauty: Towards a New Aesthetics. (New York: Allworth Press, 1998). The same is true of decon in architecture. When Bilbao was completed, instead of being seen as decon, it was received as a project to be understood solely in terms of its beauty and the transformational potential of that beauty on cities.

¶ 100 Leave a comment on paragraph 100 0 [19] Nicolas Bourriaud, Altermodern, (London: Tate Publishing, 2009).

¶ 101 Leave a comment on paragraph 101 0 [20] Mark Andrejevic, Reality TV: The Work of Being Watched, (Lanham, MD: Rowman Littlefield Publishers, 2003).

¶ 102 Leave a comment on paragraph 102 0 [21] Denise Grady, “Cosmetic Breast Enlargements Are Making a Comeback,” the New York Times, July 21, 1998, http://www.nytimes.com/1998/07/21/science/cosmetic-breast-enlargements-are-making-a-comeback.html.

¶ 103 Leave a comment on paragraph 103 0 [22] Adrienne Russell, Mimi Ito, Todd Richmond, and Marc Tuters, “Culture: Media Convergence and Networked Participation,” in Varnelis, Networked Publics, 62-66.

¶ 104 Leave a comment on paragraph 104 0 [23] Jordan Crandall, “Showing,” http://jordancrandall.com/showing/index.html.

¶ 105 Leave a comment on paragraph 105 0 [24] On surveillance art, see Thomas Y. Levin, Ursula Frohine, and Peter Weibel, CTRL [SPACE]: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002).

¶ 106 Leave a comment on paragraph 106 0 [25] Sarah Boxer, “When Seeing is Not Always Believing,” http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE5D91730F932A25754C0A9639C8B63.

¶ 107 Leave a comment on paragraph 107 0 [26] Greg J. Smith, “Burak Arikan Interview” Serial Consign. Digital Culture & Information Design, http://serialconsign.com/node/184.

¶ 108 Leave a comment on paragraph 108 0 [27] There are, to be fair, other artists working with code, most notably those, such as Natalie Jeremijenko, who explore it in a critical way, creating a critical version of maker culture. It is a blindness of this essay to not include that sort of work and the original author hopes that an astute reader/editor will add a section on this.

¶ 109 Leave a comment on paragraph 109 0 [28] See also Nell Boeschenstein, “I Want You to Want Me,” http://therumpus.net/2009/05/i-want-you-to-want-me/ for an essay embedding the work into the convoluted condition of immediated reality, including her own self-exposure and discomfort with it.

¶ 110 Leave a comment on paragraph 110 0 [29] Yunchul Kim, (void) traffic, http://www.khm.de/~tre/void.htm.

¶ 111 Leave a comment on paragraph 111 0 [30] http://www.earstudio.com/projects/moveable_type.html

¶ 112 Leave a comment on paragraph 112 0 [31] http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2007/04/27/network-maps-energy-diagrams/.

¶ 113 Leave a comment on paragraph 113 0 [32] Werner Herzog, “Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Cinema,” http://www.wernerherzog.com/main/de/html/news/Minnesota_Declaration.htm.

¶ 114 Leave a comment on paragraph 114 0 [33] Jeremy Rosenberg, “Postcard from L. A.,” Exhibitionist, http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_arts/exhibitionist/2007/07/postcard_from_l.html.

¶ 115 Leave a comment on paragraph 115 0 [34] For the Museum of Jurassic Technology and its deployment of wonder see Ralph Rugoff, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder (New York: Verso, 1995).

¶ 116 Leave a comment on paragraph 116 0 [35] Nicholas G. Carr, The Big Switch: Rewiring the World, from Edison to Google, (New York: W. W. Norton Co., 2008).

¶ 117 Leave a comment on paragraph 117 0 [36] Nicolas Bourriaud, Postproduction (New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2002), 87.

¶ 118 Leave a comment on paragraph 118 0 [37] Bourriaud, Postproduction, 39-40.

¶ 119 Leave a comment on paragraph 119 0 [38] http://www.highdeserttestsites.com/mission.html.

¶ 120 Leave a comment on paragraph 120 0 [39] Marina Fokidis, “Random Rules — Artists’ Selections from YouTube,” posted on Networked_Performance, by Jo-Anne Green (March 26, 2009), http://turbulence.org/blog/2009/03/26/random-rules-artists-selections-from-youtube/

¶ 121 Leave a comment on paragraph 121 0 [40] See Rosalind Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985).

¶ 122 Leave a comment on paragraph 122 0 [41] On remix see Edouardo Navas, “Remix Defined,” http://remixtheory.net/?page_id=3 and William Gibson, “God’s Little Toys,” Wired 13.07 (2005), http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.07/gibson.html.

¶ 123 Leave a comment on paragraph 123 0 [42] Bourriaud, Postproduction. For Bourriaud, “Postproduction apprehends the forms of knowledge generated by the appearance of the Net.”

¶ 124 Leave a comment on paragraph 124 0 [43] Bourriaud, “Public Relations,” interview by Bennett Simpson, ArtForum, (April 2001), 47.

¶ 125 Leave a comment on paragraph 125 0 [44] Bourriaud, Postproduction, 17.

¶ 126 Leave a comment on paragraph 126 0 [45] Eduardo Navas,”Andy: Meta-dandy,” http://navasse.net/star/navasWarhol.pdf.

¶ 127 Leave a comment on paragraph 127 0 [46] By this I mean they tend to be done recently but can be taken from as far back as the early 1960s, when it had become clear that modernization, in its first phase at least, was complete and the idea of “the contemporary” began to emerge. Among the first cultural institutions to recognize this, the Museum of Contemporary Art, was founded in Chicago in 1967. On “the contemporary,” see, for a start, Arthur Danto, After the End of Art: Contemporary Art and the Pale of History (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997), 10-11.

¶ 128 Leave a comment on paragraph 128 0 [47] On nostalgia in postmodernism, see Jameson, “Postmodernism,” 67. On allegory see Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” parts 1 and 2, Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 52-87. On periodization and network culture see Kazys Varnelis, “Network Culture and Periodization,” http://varnelis.net/blog/kazys/network_culture_and_periodization.

¶ 129 Leave a comment on paragraph 129 0 [48] Marisa Olson, “Putting the You in YouTube,” Rhizome.org, http://rhizome.org/editorial/2026.

¶ 130 Leave a comment on paragraph 130 0 [49] Nicholas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (New York: Lukas and Sternberg, 2002). See also Claire Bishop, ed. Participation (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006).

¶ 131 Leave a comment on paragraph 131 0 [50] Bill Wasik, “My Crowd, Or Phase 5: A Report from the Inventor of the Flash Mob,” Harper’s Magazine (March 2006), 56-66.

Wow! I’d pay good money for “a new poetics of the real” that is “distinct from existing models of realism.”

Offering to “pay good money” is kind of a “bourgeois rise to power” gesture, however, so I’ll have to settle for making this affirmative social-media comment.

But Duchamp did NOT sign it. The urinal was sent to him signed — probably by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven — as a commentary on his art practice. The fact that Duchamp exhibited it, but never gave the Baroness (or someone else if it wasn’t her) credit tells us more the devaluation of women artists and about patriarchal power structures in his day than anything.

Hayles concept of “born digital is useful in contextualising what Jodi might have meant when they spoke of “net.artists living on the net”. Prior to a certain point in time artists working with computers and associated communications technologies came to this practice from other media, employing frameworks and criteria imported from other contexts. At some point this changed and a generation of artists emerged who had always worked with digital and networked media. This didn’t happen in a simple linear manner. Nor did developments occur at the same time, or in the same way, for the various aspects of what are now, but what were not previously, related media (computers and telecommuniciations only got substantially together in the 1980′s).

There were a small number of artists working in the 1970′s who started out in their practice using digital systems, even a few in the 1960′s. There were, similarly, a small number of artists who emerged in the 80′s who were using networks from the start. Bunting is an example of this although his early network practices did not engage the internet but telephone networks. Paul Sermon is another (very different) example. However, the emergence of a generation of network savvy artists, with a culture attached, didn’t begin until well into the 1990′s. The associated buzz, involving the engagement of theorists and cultural commentators, intensified after that time. In this sense I’d assess Varnelis’s observation that these technologies “cultural implications (were) confined to niche realms for enthusiasts” more or less correct although I¹d move the dates back a little to the early 90′s or even the late 1980′s and identify 1993 as they key year in terms of impact, when the first web browser (Mosaic) became publicly available.

There were a series of events and developments, in the late 1980′s, when the key players in what was to emerge in the 1990¹s, with net.art and related practices, started to meet, communicate directly with one another and inform each other’s work. It is no accident that many of these people were Eastern or Central European or were based in what had been cold-war border cities, like Berlin and Ljubljana. A few of these artists did replay historical tropes. Shulgin’s playful refigurings of Suprematism is an example, although as much concerned with developing a commentary on his personal sense of national heritage at a time of social turbulence, post 1989, than formal art-historical deconstruction. It can be argued that the emergence of new medialities and formal frameworks are often associated with artists revisiting the past. Picasso’s confluence of Cubism and African art is perhaps an example. Again, it would be dangerous to consider this as simply or even primarily formal aesthetic experiment. Picasso, like Shulgin, lived in a social and political context and he drew inspiration from the excitement and conflict he experienced living within it.

Contemporary network culture is a very recent phenomenon. Perhaps we forget how fast things have changed and what seemed odd or futuristic to many until only a few years ago is now commonplace. There is a turbulence associated with that rate of change.

Varnelis’s piece attempts to connect artists practice with digital networks with examples of practice from a more mainstream art world (you can’t get more mainstream in the UK than the work of a Turner Prize winner). To some degree this approach is illuminating, allowing some novel connections to be made. Zittel and Auerbach’s work sits interestingly alongside Halley’s or Estes’s. It is also clear that mainstream arts practice of the early post-modern period (1960-1980) was an influence on many artists who were associated with the 1990′s emergence of art practices situated within a networked cultural context.

However, it is important to remember that many of those artists chose to work with digital and communications systems in large part because they were disillusioned with the mainstream artworld. Here I am not talking about art practices but the artworld itself. These artists sought out of a parallel system that would allow practitioners to work, communicate and facilitate new audiences without the mediation of the institutional framework the artworld was/is composed of. This activity is traceable to earlier examples, some of which explicitly join up, with practitioners associated with artist run initiatives like The Kitchen and Film-makers Coop in New York or London Video Arts and Film-makers Coop in the UK (amongst many other activities around the World during the 1960′s and 70′s) being part of the development of the prototype digital and networked culture of the 1980′s which Shulgin, Bunting and many others are associated with. This is arguably a stronger lineage of historical precedent than that which connects Peter Halley to Josh On and in this sense Varnelis’s piece risks being revisionist. But it can be hard to establish new historical connections without taking such a risk.

However, as was pointed out in the first paragraph above, nothing is linear or simple. Whilst many of the artists associated with net.art and similar activities did seek alternate models to the dominant artworld market model others sought to play with it and turn the system to their own advantage. Vuk Cosic is an example here, his provocations and interventions functioning as both critique of the dominance of market thinking in the creative arts and an attempt to grab some of the associated limelight. He played this double edged sword with some skill. It is perhaps too early to evaluate whether Shulgin’s more recent work with easy to consume electronic multiples is as clever and destabilising as Cosic’s practices (he made sense of what he was doing by Oretiring young) or whether he risks repeating the failures of Kasemir Malevich, the Suprematist Shulgin parodied in his Oform artworks, who, after a blazing period of creativity retreated into politically-correct folk-art.

To me this sort of art-historical connection evidences a “born digital” art criticism which Varnelis’s essay perhaps fails to do.

[...] entrance to this and other realms—including prominently the panopticonscious lifeworld of the immediated real. Alternate universes open up in the inframince, like an obliterati’s escape mechanisms made [...]

Is very true that ‘’digital technology is an unmistakable presence’’ in our life, but my concern is still traditions.

Do you really forgot “traditional art “or maybe you never know about it. What about art before 1900? Is only in the gallery? Who still experiment and research this old technique?

Art it been connected with technology because is “networked art”. I feel lost in this “networked art” and I still believe in “Books on Technique” and “The language of Art History”.

[...] has become a major cultural form in network culture, something I cover in my article on the immediated now. Printer-friendly [...]

[...] The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality – Networked – Excerpts [Excerpts related to Tactical Media Activism, Appropriation Art and Remix - LINK] [...]

[...] has become a major cultural form in network culture, something I cover in my article on the immediated now. Feed: tumblr [...]

[...] The technology can be replaced but the memory can’t. In his essay The Immediated Now: Networked Culture and the Poetics of Reality, Kazys Varnelis questions high and low art coming from networked [...]

[...] culture, in terms of it being a sociocultural shift that is not limited to digital technology (Varnelis, 2008)…By employing a broader understanding of the notion of network within analysis of networked [...]

I don’t think making the statement “Postmodernism called high and low into question” followed by the examples of Warhol, Kruger, Sherman, Koons, etc. is a fair one. Just because what these artists did looked like “low” does not necessarily mean that they merged or blurred the distinctions between high and low. That could have been the aim of the postmodernist theorists, but not these artists. What they did was appropriation. They appropriated what people thought would belong to high culture, hijacked them to the realm of the “high”. Warhol had a different identity as a commercial artist earlier in his career and quit to become a fine artist later, in other words he chose the “high culture” over the “low”. Likewise, Jeff Koons did not praise the kitsch as it is widely misunderstood, he simply appropriates. I think the key here is talking about these artists without considering appropriation. Neither of these are craftsman, they are not image-makers as opposed to the anonymous designers/artisans they appropriate from. In these examples, low culture creates the images for commercial purposes and high culture merely decontextualizes them. Calling this practice “questioning the high vs. low” is as ridiculous as describing Duchamp’s urinate as “blurring the boundary between plumbing and sculpture”.

[...] http://varnelis.networkedbook.org/the-immediated-now-network-culture-and-the-poetics-of-reality/ LikeBe the first to like this post. [...]

Scott Hug’s use of color from forecasting is interesting; however the word “pallet” means a wooden skid used with a fork lift. The word you need is “palette” which is a collection of colors.

[...] This is phenomenology carried out in/for globally networked culture, the seductive sedatives of immersion and haptic interfaces produce echoes and doublings that reveal the deterrance of distance, deployed to meet the demands of dromomaniacal domestics. In Pfieffer’s work, students in Manilla recite Holt’s originally off-the-cuff observations, a variant on their usual speech training exercises. All geared towards the tuning of their tongues to Americanized accents, aspiring to the preferences of call centers, and by proxy the clientele that prefer global connectivity collapsed into local linguistic cues, a kitsch variant of network realism, or a garbled dub of Varnelis’s Immediated Now [...]

[...] The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality is part or chapter of the book networked: a (network_book) about (networked_art). This particular chapter is by Kazys Varnelis. I chose to summarize and respond to the section of this chapter called Artist as Aggregator for this post. [...]

[...] article The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality has a specific section of the article that was about how people in modern culture [...]

[...] Self-Exposure section of the reading, The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality, a contrast is drawn between the reality found on television and that found on the internet. In [...]

[...] reading titled “The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality”discusses issues about the sociocultural shift from modernism to postmodernism and the shift from [...]

[...] Network art in Kazys Varnelis’, Networked The Immediated Now: Network Culture and the Poetics of Reality [...]

[...] http://varnelis.networkedbook.org/the-immediated-now-network-culture-and-the-poetics-of-reality/ [...]